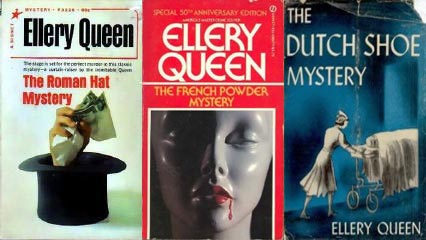

The next series of posts in the Ellery Queen series will discuss the first three Ellery Queen novels: The Roman Hat Mystery (1929), The French Powder Mystery (1930), and The Dutch Shoe Mystery (1931) principally in terms of how they negotiate the genre conventions of detective fiction.

(Since my last post, my copy of The Roman Hat Mystery has gone from “starting to fall apart” to, “well, actually, kind of fallen apart already,” as it has lost its front cover. I blame one (or another) of my cats.)

The Roman Hat Mystery is brazenly up-front about certain of its genre conventions. The victim is identified before we start the novel, and the “Lexicon of Persons” identifies all the other major players, as well—except, of course, for that small but crucial detail of whodunit. The victim, Monte Field, is utterly unsympathetic: a crooked lawyer, a blackmailer. The last thing he does before meeting with his murderer is to harass an innocent young woman.

The murderer, though, is scarcely any better. Murdering a blackmailer is one of those crimes that mystery fiction tends to be ambivalent about; some detectives will let people who murder their blackmailers go free. In this case, however, not only does Stephen Barry murder Monte Field, he also very carefully sets up a patsy to take the fall for him. And the dirt Field has on Barry is….

“Stephen Barry, to make it short and ugly, has a strain of negroid blood in his veins. He was born in the South of a poor family and there was definite documentary evidence—letters, birth records, and the like—to prove that his blood had the black taint.”

(TRHM 233-34)

And the character speaking, using hateful phrases like “the black taint,” is Ellery’s father, Inspector Queen, someone whom we are meant, in all the Ellery Queen books, to regard as both good and wise. Even when I remind myself the book was published in 1929, the racism is so alienating to me that I have trouble parsing what Dannay & Lee were actually trying to do. Obviously, the characters agree that this is a secret a person would kill to keep, but it’s also made clear that Barry is a reprehensible person. He’s trying to keep his secret from the wealthy girl he wants to marry:

“I needn’t explain what it would have meant to Barry to have the story of his mixed blood become known to the Ives-Popes. Besides—and this is quite important—Barry was in a constant state of impoverishment due to his gambling. What money he earned went into the pockets of the bookmakers at the racetrack and in addition he had contracted enormous debts which he could never have wiped out unless his marriage to Frances went through. So pressing was his need, in fact, that it was he who subtly urged an early marriage. I have been wondering just how he regarded Frances sentimentally. I don’t think, in all fairness to him, that he was marrying wholly because of the money involved. He really loves her, I suppose—but then, who wouldn’t?”

(TRHM 234)

Frances Ives-Pope, by the way, is a colorless ingenue, a kind of hangover from the Victorian Angel in the House. Her loveability—like much of the characterization in TRHM—is something we are told rather than something we feel for ourselves.

And it doesn’t answer the question of how we’re supposed to interpret Stephen Barry, who, as it happens, is almost never on stage in the novel, except as Frances Ives-Pope’s faithful fiancé—even his confession is relayed to us by Inspector Queen, not presented directly. Is his “bad blood” (and words cannot express how sarcastic those quote marks are) responsible for his bad character? Or is he a bad person who happens also to have a secret he’ll kill to keep? The novel never gives us enough information to decide one way or the other; we never get a good clear look at Monte Field’s murderer.

Ellery Queen novels tend to be a little slipshod about that part: the part where the murderer and his/her guilt should be reviewed objectively, where the evidence should stand up in a court of law. Murderers confess (as Stephen Barry does), or they commit suicide by cop, or in some other way obligingly elide the necessity of proving their guilt to a jury. Certainly, Ellery never has to testify in court at the end of one of these novels. Or be cross-examined.

And since that subject segues into a whole new can of worms—the conventions surrounding the detective and his relationship with the police—this is probably a good place to end this post.

Sarah Monette likes living in the future.